One of the perks of being a famous tree is all the documentation of your growth. Rarely are single trees the subjects of photos. Rarer still are those trees photographed at regular intervals. Archival photos of famous trees offer a chance to peek into the past and see how a tree grew from then to now.

The Lahaina banyan tree on Maui is over 150 years old. It’s blackened and scorched from the recent wildfire, though still alive thanks to immediate rescue efforts. The tree will need years of rehabilitation and close arborist attention. It’s a tough ficus. With luck, it should pull through.

I have a few banyan figs of my own, and I’ve been looking into old photographs of the Lahaina tree. Not to examine the past, but to imagine my banyans’ possible futures. If I let them follow their instincts, what shapes will they take? What feelings will they convey?

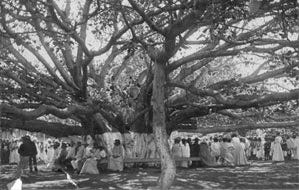

This is the earliest photo I can find. The Lahaina Restoration Foundation alleges that the tree was eight feet tall when it was planted in 1873. If we use the lounging beardocrats for scale, I’d guess this was shot 10 or 20 years later.

At this stage the tree looks like an overgrown azalea bush, not a banyan. The tips of the branches still reach upward. The limbs aren’t heavy enough to bow down yet.

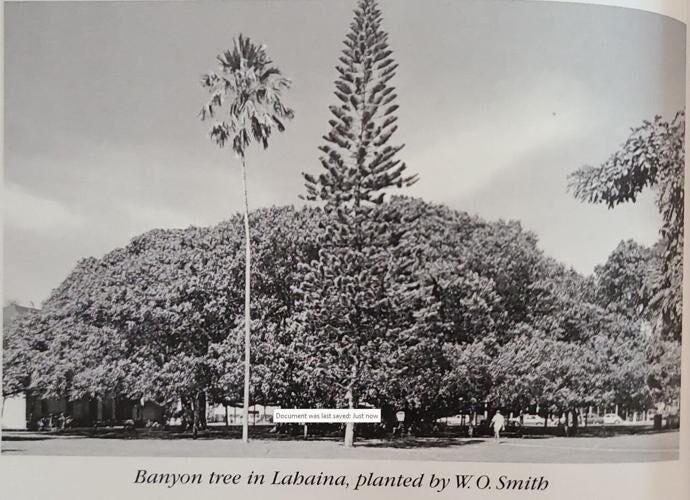

By 1908, the banyan canopy had begun to form. Instead of reaching skyward, the silhouette suggests outward creeping. The branches are beginning to creak under their own weight.

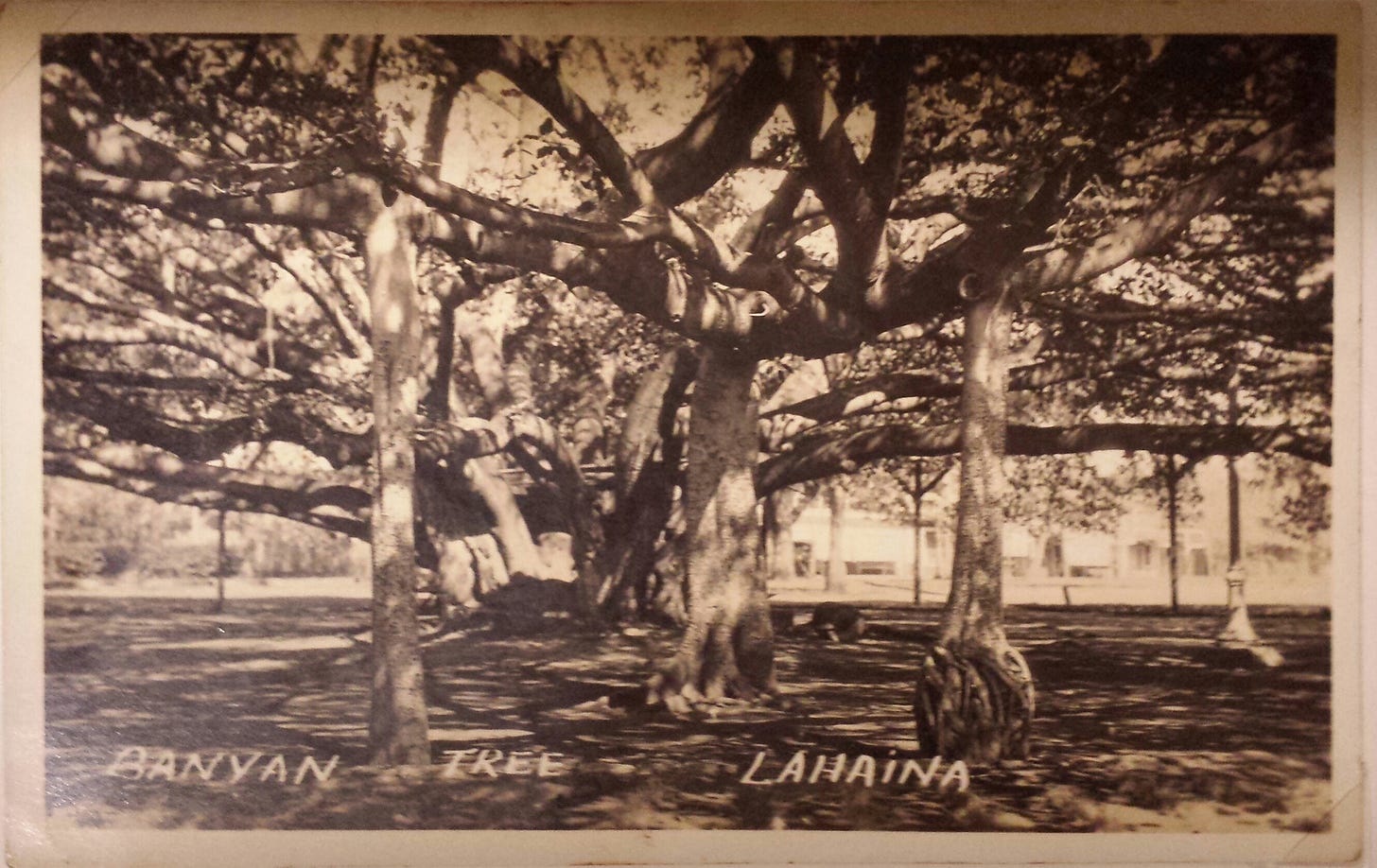

“Over the years, Lahaina residents lovingly encouraged the symmetrical growth of the tree,” says the Lahaina Restoration Foundation’s website, “by hanging large glass jars filled with water on the aerial roots that they wanted to grow into a trunk.” Trees in the aggregate might be labeled with predictable growth habits such as “globose” and “columnar,” but individual trees are inevitably shaped by their environment, intentionally and not. To me the banyan in this photo is beginning to look like a community of trees more than an individual. A fitting metaphor for the communal care that sculpted the tree into this shape.

60 to 70 years after planting, foliage near the base has shaded out and opened up to reveal a sturdy, radially spreading crown of trunks. To me this openness suggests a certain maturity and wisdom. Gone are the skinny branches of youth and their skyward aspirations. They remain only as knots in the wood.

The nice thing about living with my bonsai is that I can study them whenever I want. Sometimes it feels like too much. Every day I look at my trees and every day I imagine the possible futures of each. Anxiously, I wonder, will the trees become anything interesting? Will they turn out to be duds? What’s the right move? If this were a full sized tree in a landscape, how would it be growing? Last week I showed the evidence of style indecision with one of my olive trees. I keep changing my mind about how it should look, and each time I have less of the remaining tree to shape into something new.

I scroll through bonsai progression series on forums and blogs, and each move the artist makes looks intentional and inevitable to me. That’s the way it had to go, I think to myself. Someday I might be experienced enough to disagree with someone’s style choices, to imagine another future for their tree, but at this stage in my education, the future appears unknowable. I can imagine whatever design I like, but it’s an abstract rendering. A guess.

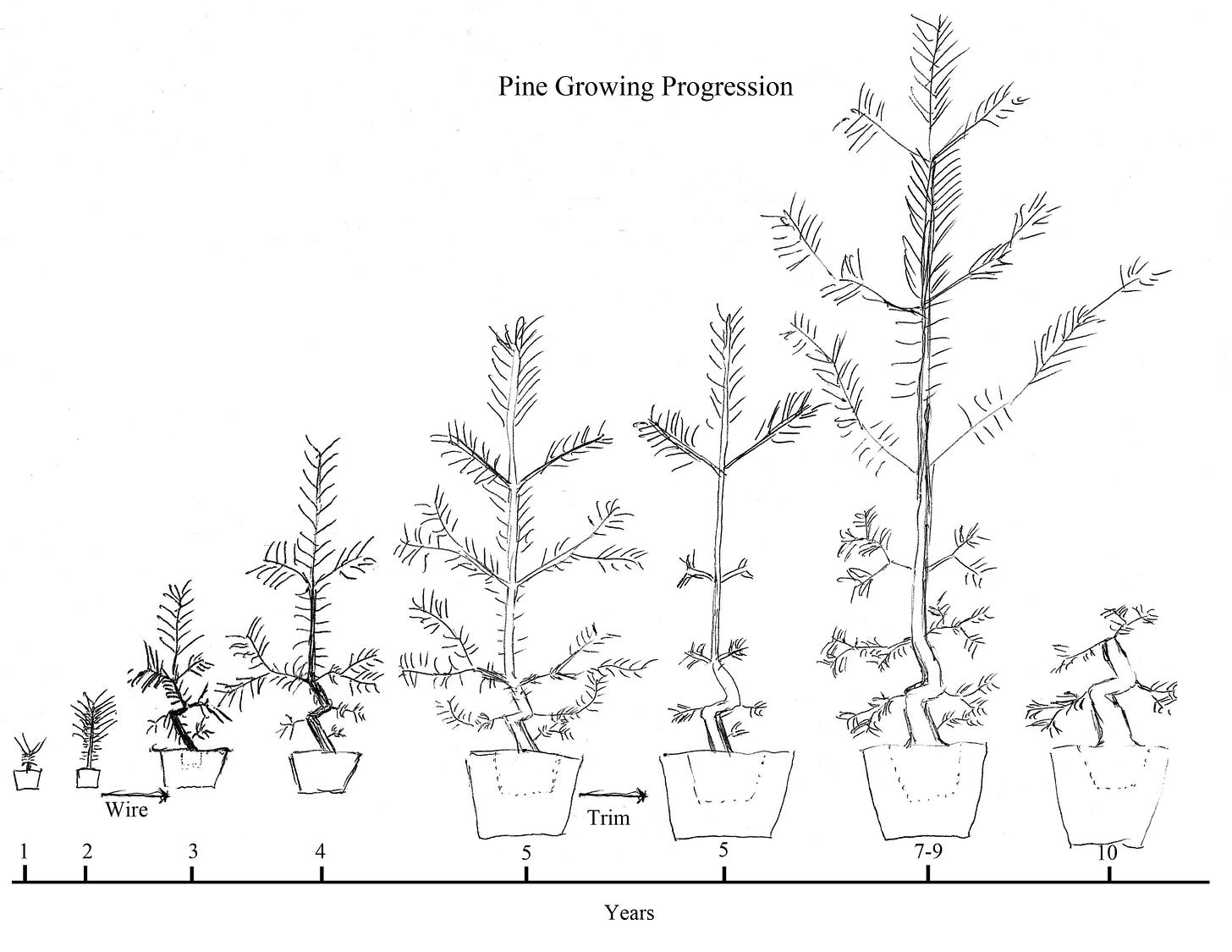

This illustration is a typical progression of a classic informal upright pine bonsai. Drawings like it were the first bonsai lesson that really sunk in, that helped me understand just how bonsai techniques work. They continue to comfort me as I regard my collection. Even if I can’t predict a future for my trees, they’re still predictable to someone else. I just need to find the pattern. Tap into the source of order.

One of my favorite Tiktok science posters named Angelo D’Argenio made a neat video about the unpredictability of the future. “We won’t ever have a Star Trek world,” he writes in the caption. “We might have something much cooler.” He brings up the real world downer that faster-than-light travel is essentially impossible, and that future humans won’t be seeking out new life and new civilizations in starships named Enterprise. “Scientific advancement fundamentally changes the way we do things,” D’Argenio says, “whereas sci-fi is focused on the way things are, just made better.” We imagine travel to other worlds in ships because we have ships now, and we can conceive of cooler ones that can cross the galaxy and host regular jazz concerts. Whatever way we wind up crossing space will, in future hindsight, seem inevitable, but as of now it’s inconceivable.

I think the art of bonsai thrives on the tension between the inevitable and the unknowable. A good bonsai design tells a story. When that story makes sense to us—adhering to our unspoken understanding of how trees look—the illusion of a miniaturized tree is a success. Yet at its best, bonsai isn’t about recreating a full sized tree at miniature scale. It’s about the idea of a tree. For that to succeed, the bonsai needs more than an authentic story. It needs to be impactful, memorable, and unique.

I’m not sure how to imagine the future of my bonsai, or if there’s any benefit to doing so. No matter what they look like in the future, the way they are now is the way they are now. The future version of me is just as alien to my present self as the future versions of my trees. I guess we’ll talk about it when we get there.

Tree reading

Hurricane Idalia sent a 100-year-old oak tree crashing into the Florida governor’s mansion. Unfortunately, governor DeSantis wasn’t injured. [CBS News]

The quest to find New Hampshire’s biggest trees. [New Hampshire Public Radio]