My friend Wei Tchou was telling me how uncomfortable she gets when people say they admire her work. Wei is a real lyrical writer, an essayist whose words reveal the magical qualities of the most material settings. She deserves all the compliments she can get. The problem, Wei said, is that people only see the output, and ignore the unglamorous, often painful writing process she goes through to get there.

“I wish I could be admired not for publishing a book or ‘making it’ in the industry,” she explained, “but for the true emotional challenges and intellectual bravery it takes to pursue the work.”

I imagine most creative people feel the same tension. Am I a writer because of the sum of my written work, or the effort it takes to produce it? The former definition turns art into a mechanistic production, and awards the largest prizes to those who can most efficiently spin words into golden thread. The latter pays respect to the labor of stabbing at your heart until the good sentences fall out, but suggests that all it takes to be a writer is to sit behind a keyboard, “creating.” Is that really enough? Is either definition?

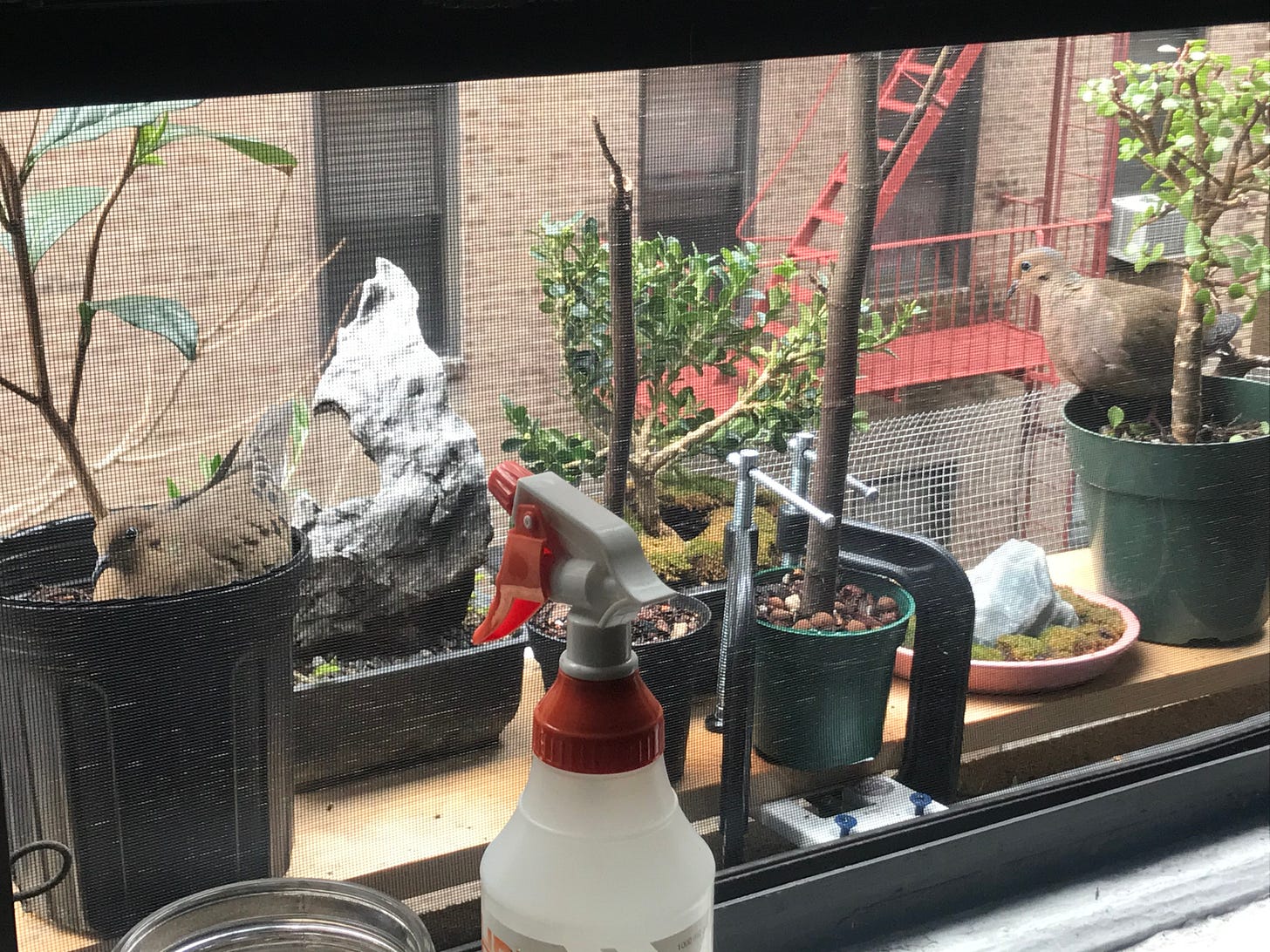

There’s no technical point at which a tree “becomes” a bonsai. Bonsai literally means “tree planted in a container.” Generally that container is wide and shallow, designed to restrict root growth and enhance the tree’s miniaturized proportions. But unless you want your tree to mature very slowly, you usually start your bonsai in a much deeper pot, or in the ground, so its trunk can thicken. Most bonsai spend decades developing this way, and only get transplanted into bonsai pots once their main features are sufficiently developed, or “finished.”

These young trees are called pre bonsai. Not yet finished. But you could leave a well developed tree in a big planter forever. At some point it graduates from pre-bonsai status into bonsai adulthood. The pot doesn’t make the bonsai.

It’s not like the work stops once you transfer a tree to a bonsai pot. You have to keep trimming shoots, raking the roots, paying attention to the tree’s needs. The tree is still growing, still becoming. Even once it’s spent decades in development and is ready to be admired, the work is never finished.

The way Tobin Mitnick puts it, you do bonsai to become a better person. The finished work is just one part of the practice, and the practice reaches fruition through the work. I think the same is true for writing, and any creative pursuit. Aristotle had a word for this: eudaimonia. I think Aristotle would have liked bonsai.

Tree reading

Reader Allie Wist shares this audiovisual, uh, experience by a group of artists who took audio recordings around a giant sequoia in Portland, OR, and translated those noises into a trippy soundscape. Note for photosensitive people: the video has rapid light flashes. [Ecology Ensemble]

Leave it to Ligaya Mishan to render chaotic bundles of tree branches into lines of beautiful prose poetry. [T]